Ports – A Brief History

Photo courtesy Port of Port Townsend

Public Benefit from Public Resources – a Brief History of Washington’s Ports

Washingtonians have gravitated to the water since time immemorial, with the earliest tribal settlements thought to have been along the Duwamish River, in the Nisqually delta area, and on the Columbia out toward the ocean. With water providing a primary means of transporting people and goods, harbor areas have long been seen as public highways to which everyone should have equal access. Since ancient times, governments at a minimum regulated navigation in their harbors, and over the years many also controlled docks, piers, warehouses, and other port facilities.

However, in the United States, as in England, the massive commercial and industrial development of ports in the nineteenth century was dominated by private corporations, especially the railroads. In the second half of the 1800s, a few U.S. cities, including San Francisco, New York, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles, took tentative steps to establish public control over some of their waterfront. But as late as 1910, just two public ports — San Francisco and New Orleans — enjoyed a “high degree of public ownership, control, efficiency and equipment.”

In 1889, when the State of Washington was officially founded, the state constitution declared that the beds of navigable waters belonged to the people and gave the Legislature power to designate which of those beds would become harbors. But industry already had a foothold, with the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway having begun in 1870. By the turn of that century, Seattle and Tacoma’s waterfronts were dominated by railroad tracks and warehouses serving private terminals and shipping lines and outfitting prospectors headed to Alaska for the Klondike Gold Rush.

In the early 1900s, across the country attitudes toward railroads and other large corporations were beginning to change. While cities owed much of their growth and development to the railroads, many that found themselves dependent on a rail line, and thus at the mercy of its rates and schedules, increasingly chafed at that dependence. Reformers, who would come to be labeled Progressives, saw public control of transportation facilities — including ports — as well as monopolies such as water and electric utilities, as the only antidote to the domination of economic and political life by private companies.

The Progressive movement and the push for municipal ownership were particularly strong in Washington, where Seattle and other cities became some of the first in the nation to establish public water and electric utilities. The struggle for public control of the waterfront was especially contentious since so many of Washington’s leading cities were ports and the economy was (as it remains) heavily dependent on trade. That struggle was largely one to win back what had been given away to the railroad companies during the long competition for the transcontinental rail connections that fueled the region’s growth.

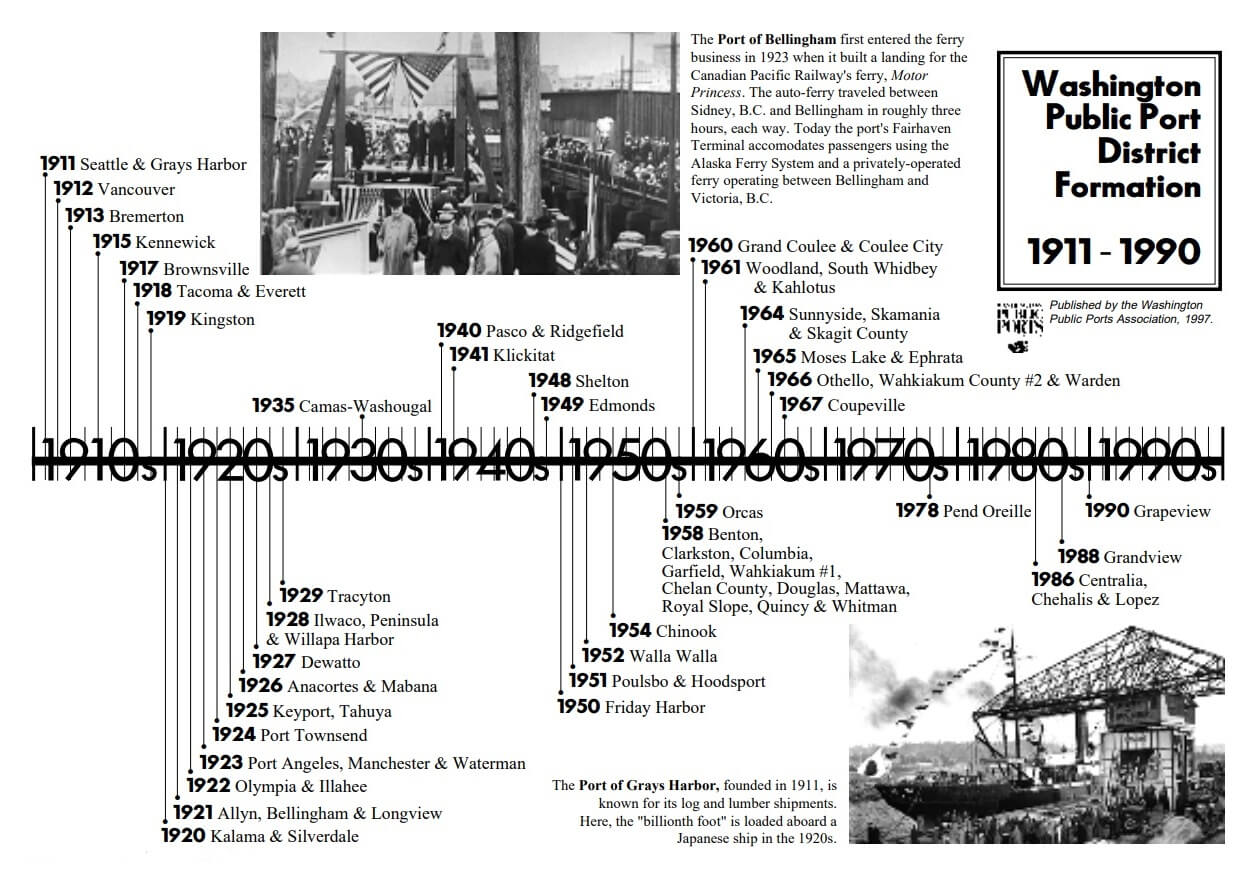

By 1911, a disillusioned public began agitating for more access to the waterfront, and those energized advocates descended on Olympia and lobbied for the right to control access to the waterfront. That year, the Legislature passed the Port District Act, allowing the people to form port districts and elect commissioners to govern them. In September of 1911, the Port of Seattle was formed, becoming the first autonomous municipal corporation in the nation to engage in port terminal operation and commerce development. The Port of Grays Harbor was formed shortly thereafter.

Since then, 75 port districts are in operation in communities all around Washington, not just near deep harbors and along rivers. From airports to agriculture transportation facilities to industrial parks, ports develop economic opportunities that are specific to the communities they serve. But wherever the port and whatever its mix of operations and facilities, each of these unique, independent local governments contribute meaningfully to the state’s healthy trade economy.

This snapshot of the history of Washington’s ports is based on a number of articles on the subject written by our friends at HistoryLink. They are a wealth of information on public ports and other topics, and we highly recommend you visit their website to learn more: https://historylink.org/

How Ports Work – Basics of Port Governance

Port districts and their governance model in Washington state are unique: where in other states they’re often departments of city government or the state, in Washington they are governed by an elected commission, independent of other local jurisdictions. Commissioners are elected to either four- or six-year terms; with the vast majority of ports being run by three-member commissions serving six-year terms. Ports of a certain size are required to have five-member commissioners on four-year terms. Commissioners may hold either district-specific or at-large positions, depending on port district policy.

Port commissions establish long-term strategies for a port district and create policies to guide the development, growth, and operation of the port. They are also responsible for a port’s annual budgets, approving tax levy rates, and hiring the professional staff members responsible for a port’s daily functions.

Port commissioners hire CEOs, Executive Directors, or Port Managers who they charge with the day-to-day operations of the port. The scope and scale of our ports is notable, with the Port of Seattle employing more than 2,000 people and operating the eighth-busiest airport in the country. Meanwhile, a fair number of ports have just one staff member executing daily operations and annual operating budgets at or under $1,000,000.

Port Financing

Ports are a unique animal – a public entity with a profit motive, referred to over the years as a “public enterprise system.” A port district’s primary goal is economic development for its community, with the end result of job creation. Initially, the port’s founding statute imbued ports with the power to operate transportation facilities to achieve that economic development aim. Over the years, those authorities have evolved, and in 1985 the Legislature formally declared economic development as an aim in itself. Beyond just basic job creation, ports pursue opportunities that will result in jobs that pay a family wage and encourage broad-based growth throughout the port district. Port districts are able to finance the long-term investments needed for such growth with four different sources of revenue: taxes, service fees, bonds, and grants or gifts.

Taxes

The Port District Act, which authorized citizens to form a port district, also authorized a tax levy to finance the district. Initially, ports were authorized to collect $2 for every $1,000 of assessed value on taxable property. The funds provided the initial capital needed to construct and operate facilities and to establish the necessary reserve of funds. Since that time, the Legislature has reduced the rate at which a port district may levy taxes (known as its “millage rate”) to $0.45 per $1,000.00 of assessed value. In addition, special property tax levies are authorized for additional purposes, including dredging, canal construction, land leveling or filling; and general industrial development. These levies cannot exceed the 45 cents per $1,000 millage rate.

Most ports use the funds generated through the tax levy to pay for capital development – marine terminals, industrial parks, development of needed infrastructure, updated airport facilities. Investment in these facilities is necessary to attract and retain businesses to a region, and lease rates and revenue from property sales is returned to the district to be reinvested in future development projects.

Ports pay sales taxes on their purchases and also pay a business and occupation (B&O) tax on services they provide to their customers. Businesses who lease port property pay a leasehold excise tax, approximately equal to the property tax they would be assessed if the property was privately owned. Ports collect these taxes on behalf of the state, and the funds are distributed back to state and local governments. The tax revenue generated by port operations is one of the major ways in which they promote prosperity in the communities they serve.

Bonds

Ports may issue a variety of municipal bonds – these bonds are used almost exclusively for capital construction projects. The bonds are repaid with revenue from property taxes. Ports may also issue revenue bonds, which are guaranteed by the revenues generated by a specific project. Bonds provide the funds for a port district to make a major, long-term investment in infrastructure – an investment which typically benefits a community for decades to come.

In very specific situations, ports may also establish a special assessment to issue industrial development revenue bonds. These bonds do not generate revenue for the port; rather, they provide a way to finance development or expansion of industry within a port district. The bonds are issued for a specific company, and that company is responsible for payment. No taxes or port funds are used to retire these bonds, which are subject to strict federal guidelines.

Grants And Gifts

Ports may use a variety of grants or gifts, such as property, to support infrastructure development. For example, in 1998 the Port of Benton was deeded more than 750 acres from the U.S. Department of Energy, on top of the more than 300 acres of federal government property they’ve acquired since their founding. The Walla Walla Airport, and surrounding industrial properties developed by the port, were surplused by the Air Force in 1947 and operated as a city-county facility until the port took over operations in 1989.

In addition to surplused property and transfers, ports may receive federal funding for projects from agencies like the Army Corps of Engineers and the Department of Transportation. Washington ports also receive funds from the state, particularly from the Department of Commerce, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Ecology the Community Economic Revitalization Board, and the Recreation and Conservation Office. Funds come as grants for transportation projects, for environmental cleanup, and for community projects including docks and boat launches; while grants loans through CERB can help ports attract new private-sector partners, develop facilities that have long sat vacant, and otherwise accommodate community demand for new economic activity.